6. How long was it between the time when the supposed supernatural events took place, and when they were first written down (in a document that has had copies of it preserved). Is it early enough to suggest the text is based on testimony rather than later legends?

Last time, we looked at the ancient religions of Hinduism and Judaism, which make claims about events taking place long enough ago, that there is room to doubt or deny the very existence of their foundational figures. But even in the case of founders who clearly existed in historical times, there is often a significant gap of centuries between the time they lived, and the time in which the accounts (or legends) about them were written down.

(This particular post will not focus on religious founders during the modern era, e.g. Joseph Smith, for whom lots of contemporary documentation still exists. Modern founders can usually pass this test fairly easily, although in many cases the contemporary material is sufficiently embarrassing that these religions might have been more plausible if less contemporary material had been preserved...)

Pali Canon (gap of centuries)

I'm no expert on Buddhism, but I gather that the earliest texts seem to have been written down quite a long time after his death. First of all, Buddhist traditions can't even agree on which century Gautama Buddha lived in; some traditions say 563-480 BC, others say 483-400 BC. (Although, if you think that's bad, the scholars can't even agree on which millennium Zoroaster lived in!)

According to Gautama's Wikipedia article:

Various collections of teachings attributed to him were passed down by oral tradition and first committed to writing about 400 years later.

although the article on the Pali canon (the earliest collection of Buddhist scriptures, compiled by Theravada tradition) suggests that a few of the books may have been fixed by the reign of Ashoka (268-232 BC).

Because these are some of the earliest documents we have about Buddhism, in the other parts of this series I will be implicitly assuming that the Pali canon contains a more or less authentic account of Buddha's teachings. But it should be kept in mind that we still have them at a significant remove.

This is a significantly longer period of time for legends and accretions to develop, compared to the interval of 20-30 years between e.g. Jesus' Resurrection and St. Paul's letters.

Lotus Sutra (more centuries, also snake people)

Other Buddhist texts were written much later still, and have no good claim whatsoever to be based on the life of the historical Buddha. For example, one of the most popular Buddhist religious texts outside the Pali canon, the Lotus Sutra of the Mahayana tradition, teaches the inspirational doctrine that anyone who seeks Enlightenment can eventually become another Buddha, helping others in turn. This text has the following origin story.

The tradition in Mahayana states that the sutras were written down during the life of the Buddha and stored for five hundred years in a nāga-realm [i.e. a parallel world populated by snake gods]. After this, they were reintroduced into the human realm at the time of the Fourth Buddhist Council in Kashmir.

which hardly inspires confidence that the text really represents the authentic teachings of the historical Gautama Buddha. (Would you trust a snake-person to accurately copy a manuscript?) It takes only a small modicum of skepticism to suspect that this document was actually written around the time of its supposed "reintroduction to the human realm", which if the above account is correct would have taken place c. 78 AD or c. 127 AD depending on when Emperor Knishka took the throne, approximately 5 or 6 centuries after the death of Buddha).

If my argument in the previous installment was right, the fact that the Lotus Sutra is legendary should also be pretty obvious from its contents and style, since it is very hard to spin convincing fake histories out of whole cloth. Let's see if this suspicion bears out.

This text opens with the Buddha surrounded by (if I've looked up the terms correctly) over 12,000 fully enlightened monks, 8,000 additional monks and nuns, 80,000 irreversibly enlightened bodhisattvas, 42,000 heavenly deities of various kinds, hundreds of thousands of snake-gods, millions of horse-headed deities, bird-headed deities, nature spirits of different kinds, and oh, a few hundred thousand normal humans too. (One wonders who was doing the catering for this event?) At this time, the Buddha emits a ray of light from his forehead that illuminates the entire multiverse. The crowds then listen to him expound his teaching of the sutra for 60 small kalpa [i.e. aeons lasting billions of years], before he passes into Nirvana.

It is hard to take this seriously as the recording of a historical event. To be very clear, my reason for saying this is not that the text contains a supernatural event. (The Bible also contains supernatural events.) Nor is the problem that the supernatural events described contradict my Christian worldview. (That would be circular reasoning, if we are trying to figure out whose religion is most plausible.) Rather, the problem is that the text makes no attempt whatsoever to fit the supernatural events into a plausible historical narrative that fits within the space and time parameters of the historical Siddhartha Gautama's life, the monastic teacher who lived for 83 years (not billions of years), during which the population of India probably did not include millions of people with animal heads, at least according to our current archaeological understanding.

Thus, it's not so much that the Lotus Sutra tries to be historically plausible, but fails to be fully convincing due to a few minor slip-ups about details. As far as historical accuracy goes, this document is not even competing in the same tournament as the canonical Gospels! Given its legendary nature, any spiritual value it has can only survive if the text is capable of standing on its own independently, apart from being historically grounded in the words of the actual Buddha. But for this particular text, I don't see how that can work very well, since a lot of the content of the Lotus Sutra consists of specific promises supposedly made by the Buddha to his disciples, on the basis of his preternatural wisdom. If the Buddha didn't actually make these promises, then what reason do we have to trust them?

(To Christians, the Lotus Sutra is also noteworthy in that it contains an alternative version of the parable of the Prodigal Son. Because of the greater complexity of the Buddhist story, my personal opinion is that the Christian version probably came first; not that it matters much theologically, because we already know that Jesus sometimes adapted illustrations from other sources. The Buddhist version of the tale is notably different though, in that the father only becomes wealthy after the son departs. Also, in the Buddhist version the son really is taken on as a hired servant; not because of any defect in the father's love, but rather because the son is skeptical that the rich man is actually his father, so the father devises it as a clever scheme to gradually entrust the son with more and more privileges, so as to eventually restore the relationship.)

The Miracles of Zoroaster (gap of millennia)

With regard to the miracles of Zoroaster, the (non-religious) Encyclopædia Iranica says:

These miracles do not reflect historical events; they are always associated with the mythical and legendary history of Mazdaism and the ancient Iranian epic, although the miracle itself remains, as in other cultures, an act contrary to the laws of nature or one attributable to divine intervention (Sigal, p. 10). One might even say that there is no hagiography in Iran comparable to that which grew up in Christendom or in Islam. Even though Zoroaster can be considered a saint, the legends concerning his life and miraculous deeds are probably of late origin. They are not comparable to the miracles attributed to Jesus and his disciples, nor indeed to those attributed to Christians martyred under the Sasanians (see Gignoux, 2000). The invention of miracles in Mazdaism may be the result of competition towards the end of the Sasanian period with other established religions (i.e., Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), the aim perhaps being to show the holiness and eminence of the founder of Zoroastrianism; such hagiographic traditions can scarcely have survived for more than a millenium...

The sources concerning Zoroaster... and others are Dēnkard V and VII, the Wizīdagīhā ī Zādspram (see ZĀDSPRAM), and the Wizīrkard ī dēnīg. No historic accounts exist of the life of Zoroaster. The Mazdean theologians formulated pious legends, mainly based on their own imaginative perceptions, although one may surmise the existence of lost parts of the Avesta or the Zand that would have attested them. The existence of many variations between the texts may be construed as evidence of their authenticity, or merely an indication that there was competition to relate the most striking and demonstrative miracles. [bolded emphasis mine.]

Of the three sources mentioned above: the Zadspram dates to the 9th century AD; the Denkard dates to the 10th century AD; and the Wizīrkard ī dēnīg has an extremely controversial and convoluted textual history. Although the story of Zarathustra’s life is narrated by Medyomah in the first person, the transmission of the manuscript can only be traced back to 1239 AD (and even this date is controversial, since when the text was published in 1848 it was rejected and suppressed, leading to the destruction of most copies of the text).

To summarize this data: Zoroaster died somewhere in the range 1500 - 600 BC. The earliest accounts of his miracles seem to date to the 800-1200's AD, which is approximately two thousand years later, in texts that written during the dominance of Christianity and Islam, when Zoroastrians needed to show that their religious founder was just as cool as those other religious founders. In this case the gap is too large to take the claims seriously.

The Oral Torah (a millenium and a half)

Rabbinic Judaism also has some relatively unconvincing claims of oral transmission from the past. It claims that its interpretations of the Torah (which are compiled in the Talmud, the first layer of which was written down c. 200 AD) are based on an unwritten "oral torah" given by God to Moses himself, more than fifteen centuries earlier. Even though we have no records of anyone talking about the oral torah before about 150 BC, when the party of Pharisees began to exist! This is staggeringly implausible, not just because of the lack of references in the written Torah to this supposed secret tradition, but also because of the tumultuous history of the Jews described in the Bible, during which the written Torah barely survived intact.

(Incidentally, Jesus was vehemently opposed to these oral traditions of the Pharisees, even though in other respects his theology was in closer agreement with the Pharisees than the other Jewish sects of the time. After the destruction of the Temple, the Pharisees and Christians were the two main sects of Judaism that survived. Although in medieval times, there was a significant sect of Jews who rejected the oral torah, called the Karaites.)

Orthodox Jews believe that the Great Sanhedrin (i.e. the supreme council of 71 rabbis who judged the most important religious cases, which existed until 358 AD), goes back all the way to the time of Moses. The Torah does say that there were 70 elders who received the Holy Spirit at the time of Moses, but there is no statement that this was intended to be a permanent body, nor are there any references to the Sanhedrin before 76 BC. Prior to the Babylonian Exile in 605 BC, decisions about the law seem to have been normally rendered by priests, not by rabbis (who did not exist before the Exile, and who therefore also do not have an unbroken chain of ordination going back to Moses).

The New Testament (decades)

In the case of the New Testament, the exact dating of the Gospels is somewhat controversial, but it is pretty uncontroversial to say that they are all products of 1st century Christianity, which places them no more than 70 years after the death of Jesus c. 33 AD. (Some unusually skeptical scholars date the Gospel of John to the early 2nd century, say 110 AD, but I believe this is currently a minority opinion.)

I personally think the Gospels were probably written significantly earlier than this. For example, one of the main reasons these scholars date the Synoptic Gospels to after c. 70 AD, is that in them Jesus predicts the destruction of the Temple at Jerusalem, about 40 years before it happened. But this argument seems to rest on the anti-supernaturalist assumption (sometimes called "Methodological Naturalism") that historians should never accept supernatural explanations on principle. These scholars are basically asking the question: "Given the premise that predictive prophecy is impossible and that Christ didn't really say this, when did this text most likely arise?" But that would be circular reasoning, if we are trying to decide which if any religion is believable in the first place!

(Sure, if a scholar has other reasons to believe Christianity is false, it would be completely rational for them to ask what historical conclusions would follow from that. But the scholarly constructions of such hypothetical scenarios, are almost always presented to the public as if they were a refutation of Christianity based on definite historical evidence, instead of what it almost always is: a speculative historical reconstruction based on the assumption that Christianity is wrong.)

Without such biased assumptions, it is just as plausible to suppose that the Synoptic Gospels were written more like 30 years after the death of Jesus, and the Gospel of John perhaps another decade or two after that. Especially if the Gospels were actually written by their traditional authors Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, as testified to by nearly all subsequent Christian writings to discuss the question, beginning in the 2nd century. Earlier dates are also suggested by the kind of indicators of historicity I described last time.

One can argue for a more conservative point of view as follows: The book of Acts (a text in the New Testament describing the early history of the Christian Church) highlights the missionary work of Sts. Peter and Paul, but strangely ends at an anticlimax (St. Paul is in Rome awaiting trial, but hasn't yet been tried by Caesar or executed). One can think of several possible explanations for this omission, but the simplest one is that these events hadn't happened yet. This would put Acts in the early 60's at the latest. But Acts is a sequel to the Gospel of Luke (by the same author), and Luke's Gospel is generally believed to have used Mark as one of its sources. This would probably push Mark back to the 50's AD, i.e. less than 30 years after the Crucifixion of Jesus. (I don't claim that this argument from silence is completely watertight, not at all; but the arguments for later dates are at least equally indirect and circumstantial. What's sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander.)

To a young person, a few decades may seem like a long time—but actually this is really good by the standards of most ancient historical texts. It means that the New Testament was written down when at least some of the people who had witnessed the key events were still alive. Similarly, most scholars of ancient literature would probably kill to get multiple sources identifying the author of their favorite text from the century after it was written.

On the other hand, the surviving Gnostic Gospels were all written much later, mostly in the 2nd-4th centuries. A possible exception is the Gospel of Thomas, which could be from the 1st century, but is more usually dated to the 2nd.

The letters by St. Paul are dated (depending on the letter) in the interval between the late 40's and his martyrdom in the early 60's. Secular scholars generally think only about half of the 13 Pauline epistles in the New Testament were actually written by him (opening the door to later dates for the rest of them). I would dispute this judgment, but it is not of great importance in this context, since the most important letters from the point of view of Christian apologetics mostly belong to the undisputed category. (Although if 1 Timothy is authentic, it would give another reason to date the Gospel of Luke earlier than Paul's death, since 1 Tim 5:18 appears to quote from Luke as if it were already authoritative Scripture.)

One particularly important passage (in a letter that is undisputedly by St. Paul himself) recites a long list of eyewitnesses to the Resurrection of Jesus:

For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas [i.e. Peter], and then to the Twelve. After that, he appeared to more than five hundred of the brothers at the same time, most of whom are still living, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles, and last of all he appeared to me also, as to one abnormally born. For I am the least of the apostles and do not even deserve to be called an apostle, because I persecuted the church of God. But by the grace of God I am what I am, and his grace to me was not without effect. No, I worked harder than all of them—yet not I, but the grace of God that was with me. Whether, then, it is I or they, this is what we preach, and this is what you believed. (1 Cor. 15:3-11)

By cross-referencing Paul's ministry to other historical events, this letter is usually dated c. 55 AD, that is about 25 years or so after the claimed appearances. It implies that St. Paul was given a list of individuals and groups who encountered the resurrected Jesus before he himself did (although he omits the women who were the first to see Jesus, possibly because the ancient world, being sexist, did not take the testimony of women as seriously).

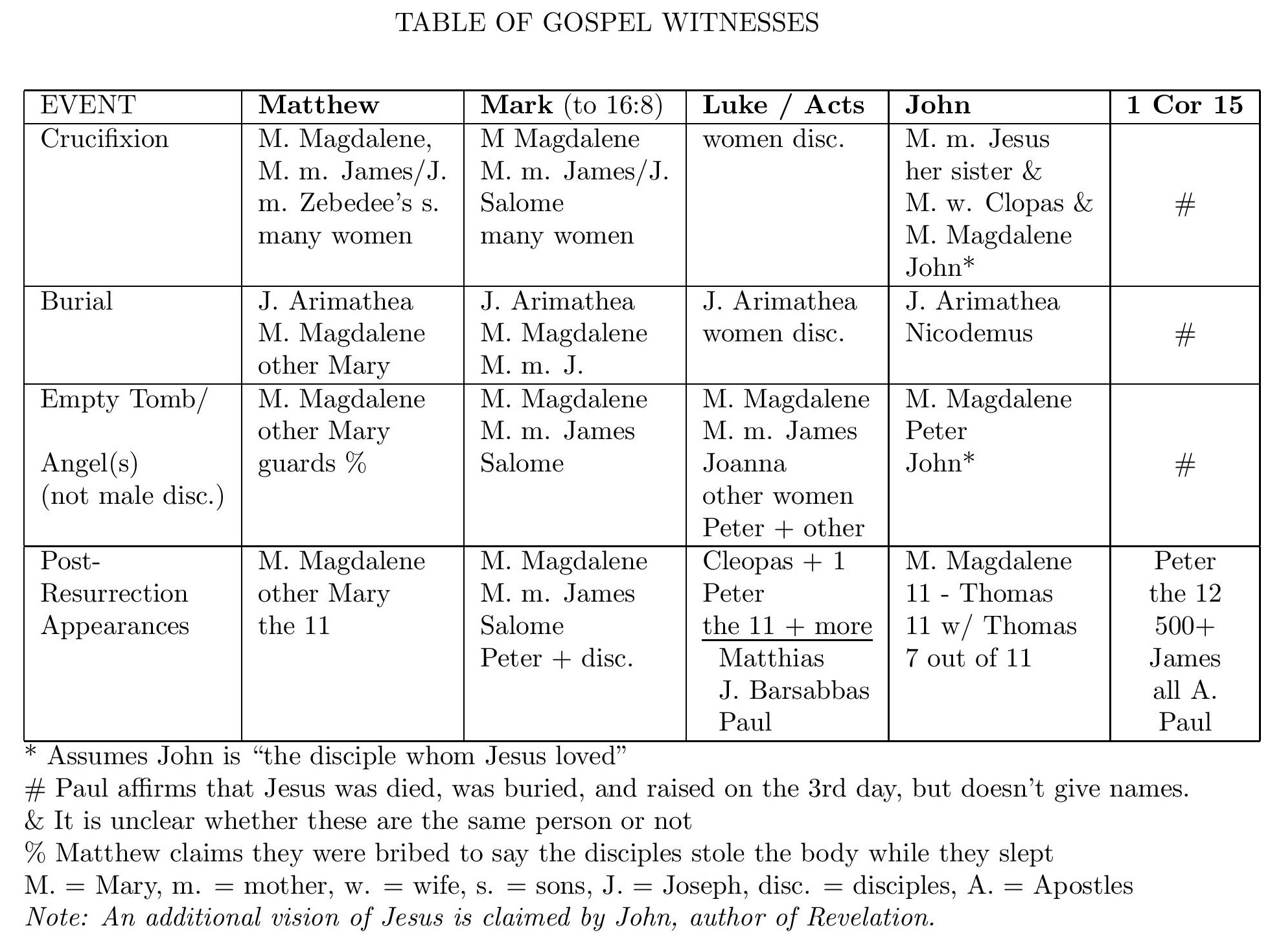

To get more detailed information about what actually happened during several of these appearances, you have to read the Gospels or Acts. (No one source gives all of the Resurrection Appearances, but several Appearances seem to be described by multiple sources.) This data is summarized in a table at the end of this post.

A Note about my Methodology

I'd like to make a slight digression about my methodology at this post, in order to highlight at least one potentially biasing factor in my own research.

In the last section I questioned the anti-supernaturalist assumptions of biblical critics. But I only know about these circular assumptions because I've investigated the Christian religion closely enough to have my own opinions.

On the other hand, for most of the other religions in this section like Buddhism, I have had to rely on the dates given by supposedly objective "neutral" scholarship as summarized by e.g. Wikipedia. On the other hand, I would never rely on the supposedly "neutral" scholarship on Wikipedia in the case of Christianity, which I consider to be tainted by its deference to secular biblical scholarship. So is this a fair mode of proceeding?

Well, one possible answer is this: given my current level of knowledge of other religions I don't see much alternative, so it will have to do for now. But if anyone is aware of evidence that other religious texts are dated in a way which is also cynical and biased against the claims in question, they are welcome to present this evidence in the comments.

And I do think I am able to reject similarly specious rejections of religious histories when I encounter them in the wild. For example Patricia Crone, a highly respected Islamic Studies scholar at the IAS, seriously argued that Mohammad never really lived in Mecca. This is exactly the kind of bizarre reinterpretation of Islamic history which I would never accept in the case of Christianity, and indeed I don't accept it for Islam either!

Also, even if I were to take the views of secular biblical critics at face value, the gap before the New Testament was written down would still compare very favorably to all of the cases reviewed above, where the record gap is much longer. (The large majority of secular biblical scholars date the Gospel of Mark to c. 70, which is still only four decades after the death of Christ, i.e. within the lifespan of a single individual. And this document is filled with lots of different miracles.) So I think an apples-to-apples comparison still ends up with Christianity coming out looking very favorably on this point, compared to other ancient religions.

(By the way, I don't think my rejection of manuscripts that were supposedly preserved by snake-people in a parallel universe, or manuscripts written on golden plates that are invisible almost all the time, counts as a similarly pernicious methodological assumption. There's a big difference between: 1. being open-minded enough to potentially accept manuscript evidence for supernatural claims if the texts bear the marks of being actual historical documents, and 2. being so gullible that you'll accept documents written by people who basically said to their contemporaries: "No, you can't see the previous manuscripts, they were invisible the whole time because of this additional supernatural event, an event which makes it so this totally isn't a situation where I just wrote this document right now and tried to pass it off as a lot older than it actually is".)

The Quran (effectively contemporaneous)

We now turn to the most recent of the large world religions. According to Islam, the primary source of religious knowledge is the Quran (supplemented by traditions called Hadith, see below). The Quran itself was extensively memorized by a large number of people, and written down not very long after Mohammad's death.

The evidence does not seem to support the extravagant claim by orthodox Muslims that the Quran was preserved perfectly, since there is plenty of evidence for variant readings among early Muslims. (Mohammad is said to have explained some of the variant readings among different Muslim groups by claiming that the Quran had been revealed in 7 different Arabic dialects, but this could easily have been an ex post facto rationalization in order to keep peace in the community.) Also, the third caliph Uthman ordered the destruction of all versions of the Quran except a standardized edition, thus removing most of the evidence of early variations. From a scholarly perspective, this is the worst possible way to make the exact contents of the text certain.

Nevertheless, the Quran was likely still preserved with a very high degree of accuracy, due to the large number of listeners who memorized, recorded, and preserved it. So I think we can trust that the version we have today is extremely close to the words that Mohammad himself spoke. Thus, for the practical purpose of deciding whether Islam is true, I think we can take the text of the Quran for granted as being nearly identical to the version spoken by Mohammad.

(As stated in the last section, I am assuming that the standard outline of Muslim history reported by Muslims is basically accurate in its broad outlines, and there are no giant conspiracies to make up entire cities and dynasties during the period after Mohammad. Which is not to say that there are no legends or exaggerations, or that facts are not recounted from a specific viewpoint. I think this is entirely reasonable and fair, given the number of people involved and the fact that it was founded during historical times. I don't think weird revisionist theories of early Islam should be taken seriously, any more than weird revisionist theories of early Christianity.)

So far, so good. However, the purpose of this exercise was to assess the credibility of specific supernatural claims, not merely to assess the evidence for the mere historical existence of the religion itself at the time of its supposed founding.

And for the most part, the Quran itself doesn't record any miracles actually done by Mohammad. In fact there are a great many disavowals of the miraculous, in which he explicitly refuses to perform miracles! (On occasion, the Gospels also record Jesus refusing to perform miraculous signs to convince skeptics, yet there are far more incidents described where Jesus does perform dramatic miracles, usually out of compassion for suffering people, and often in the presence of his enemies.)

There are three noteworthy exceptions:

(1) The Night Journey in which Mohammad was taken from Mecca to Jerusalem, described for example in the following verse:

Exalted is He who took His Servant by night from al-Masjid al-Haram to al-Masjid al-Aqsa, whose surroundings We have blessed, to show him of Our signs. Indeed, He is the Hearing, the Seeing. (Sura 17:1)

Later traditions (not found in the Quran) say that the journey took place on the heavenly steed Buraq, and that in his journey Mohammad also ascended to Heaven, where he met with a series of previous prophets. Suspiciously, no one on Earth witnessed any of this besides Mohammad himself, so mostly we are left with his bare claim to have done this.

(2) The Splitting of the Moon is mentioned in just 2 consecutive verses of the Quran:

The Hour has come near, and the moon has split. And if they see a miracle, they turn away and say, "Passing magic." (Sura 54:1-2)

If it weren't for later traditions (see below), it wouldn't be 100% clear that this is supposed to be a sign at the time of Mohammad's ministry (a few Islamic commentators have thought that this text refers to a sign that will take place in the End Times).

(3) The primary miracle of Islam is supposed to be the literary beauty and inimitability of the Quran. This has always seemed unconvincing to me as a supernatural sign, since there have been many other brilliant poets in history with rough backgrounds. And as far as I can judge personally from English translations, while parts of the Quran certainly have a forceful grandeur (e.g. the magnificent Rolling Up Sura), taken as a whole I do not get the same impression of stylistic beauty that I get from many other poetic books.

Admittedly, I don't know what it's like in the original Arabic. (I was never very good with foreign languages, so I'm not going to try to learn it either.) Most Muslims would say that this doesn't fully count as reading it, and I can certainly believe that it sounds far better in the original.

But this is yet another way in which Islam, despite its attempt at universalism, is much more bound to a particular culture than Christianity is. We accept translations of the Bible in all languages, because Christ is for everyone! And while no translation can capture all of the stylistic features of the original, quite a bit of the poetic beauty of e.g. the Psalms and Isaiah comes through just fine in English translations.

Hadith (a couple centuries)

There are also several reports in the Hadith (later oral traditions about Mohammad's words and deeds) that Mohammad did miracles. Now, the major collections of hadith were not written down until a couple centuries after Mohammad's death, and there are typically several people in the chain between the first person who wrote it down and the prophet. So far this may not sound all that impressive...

...but on the other hand, many of these traditions are recorded by multiple lines of transmission. For a few hadith, there are so many independent chains of transmission that it is essentially impossible for a reasonable person to doubt their validity. For other hadith, there is only a single chain of transmission, so you have to decide whether you think that the narrators were trustworthy. Muslim hadith scholars have taken great pains to try to separate out the reliable from the unreliable hadiths, by checking the accuracy of all the individuals responsible at each step of the chain of transmission (although in Sunni Islam, the Companions of Mohammad himself are pretty much just axiomatically assumed to be reliable, which is potentially problematic for those who do not already accept Islam). In many ways, their minimal threshold for accepting hadith as reliable are quite impressive—if also somewhat legalistic and rigid.

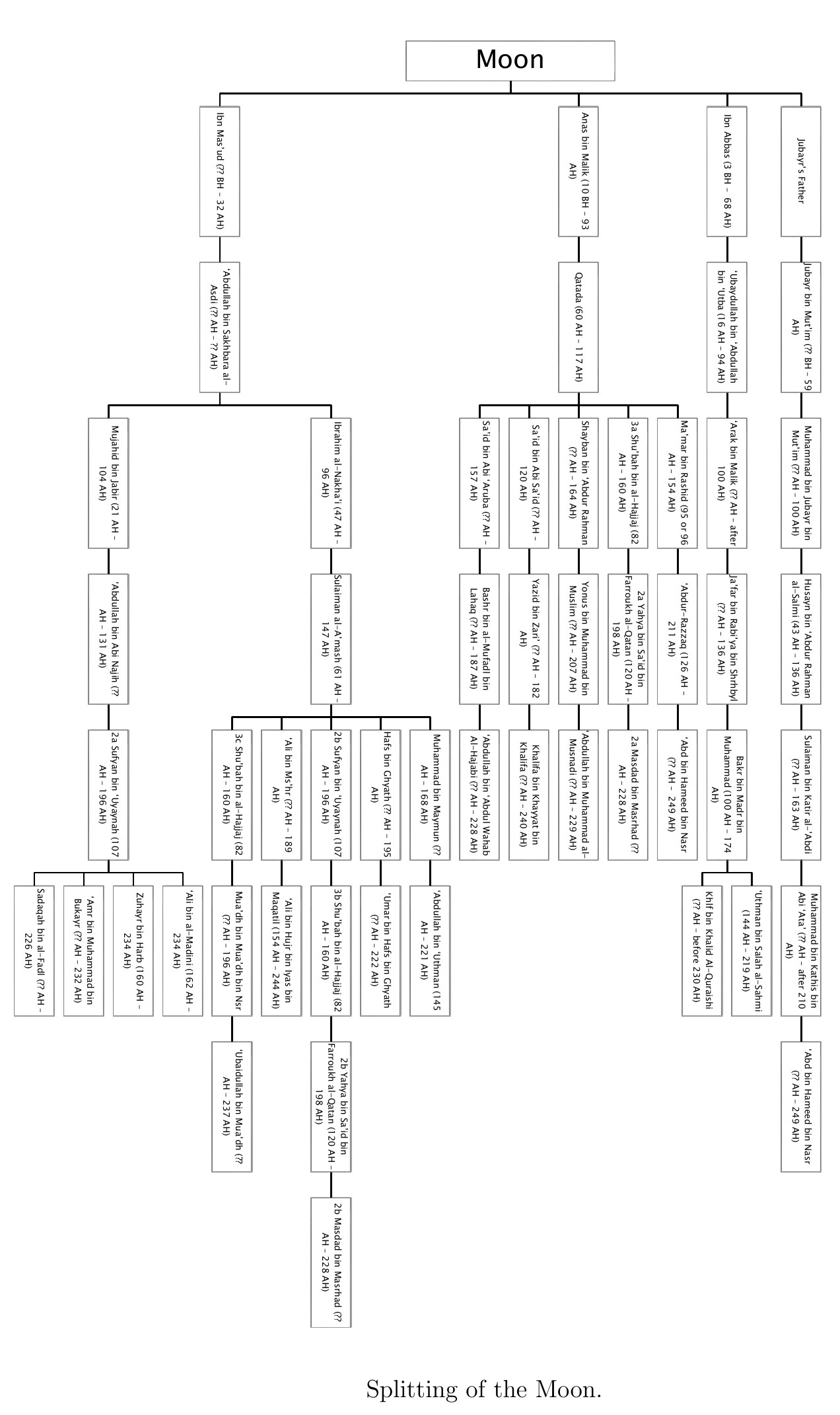

At the end of this post I will insert a "tree diagram" showing the chain of transmission for the hadith for the Splitting of the Moon, which is one of several miracles attributed to Mohammad in Hadith.

Comparison between Christian and Islamic miracle sourcing

While the 2nd century testimony for e.g. the authorship of the Gospels is quite good by the standards of ancient history (when it comes to nonbiblical texts, scholars are willing to accept authorship claims with far less evidence), as an apologist I can only wish that the early Christians put as much attention into explicitly recording chains of transmission as the early Muslims did.

On the other hand, there was also less need for them to do so. The writers of the Gospels and Acts were writing within a few decades of the events they wanted to record, and—operating within the usual conventions of Greco-Roman biography—they found it sufficient to merely name some of the individuals who were present at each event, with the implication (normally unstated) that some of these individuals were sources for the historian. What we are really seeing here is the distinction between a literate culture and an oral culture.

Since the Gospels were preserved in an essentially fixed form before the first generation of witnesses had died out, there was not the same need to construct elaborate chains of transmission, when the written documents came from the Apostles themselves or their close associates.

So I don't think that the miracle reports in the hadith can be casually ruled out as later legends. But that does not mean I am willing to concede that these miracles actually happened. (See the next question).

In order to facilitate a head-to-head comparison between the Resurrection of Jesus (the most important Christian miracle) and the Splitting of the Moon (which I consider the most impressive Islamic miracle of those that are well-attested), I include the following two charts, giving the witnesses associated with each miracle claim:

[I am grateful to my friend Ahmed for providing me with the following "tree diagram" illustrating the chains of transmission for the "Splitting of the Moon". The top 4 names are those who are claimed to be direct eyewitnesses of the miracle, while the bottom names are the last members of the chain, whose testimony was recorded in early, reputable hadith collections along with the chain of narrators]

Next: Natural Inexplicability

Wow Aron, removing my post and ignoring my e-mail.

Dear Aron please feel free to e-mail me. However I do think that you have made an error here.

Mark,

I did not remove your post. Originally, your post ended up in the spam filter, through a mistake in the spam software, which frequently incorrectly flags legitimate posts as spam. (This blog gets more than a thousand times as many spam comments as real comments, so I have no choice but to use automated software.)

I restored your original comment from the spam filter just as soon as I got your email, but by that time you had already left multiple versions on different posts, so I had to clean up after you as best I could. I started by deleting all but one copy of the multiple copies of the same comment that you posted to different articles--please don't do that, by the way!

Since your comment was off-topic for this post, in violation of item #2 of my comment policy, I then moved the single remaining version of your comment to the actual blog post that you were responding to.

Finally, I replied to that comment there.

Please make an effort to familiarize yourself with the rules of this place before assuming that I'm out to get you. If you were invited to a dinner party, you probably wouldn't just walk up to the host and start insulting him as soon as you arrive. It's the same with a blog comment section.

There is no social rule that states that busy academics have to drop everything they are doing in order to reply immediately to anyone who sends criticism to their email inbox or blog. I contemplated deleting your comment altogether, because of its uncivil tone, but you raised enough substantive physics issues that I decided it would be better to reply. God bless you.

Aron,

When you say "Luke's Gospel is generally believed to have used Mark as one of its sources" don't people say this because of the same fallacy you detail above, i.e. Methodological Naturalism? When a textual critic says that Luke is based on Mark, it is part of their chain of presuppositions that include that Mark and Matthew draw from the hypothetical "Q document" and their reasoning for this is that there must be some other document that is wholly true and thus does not contain miracles. They do not for instance accept the idea that Luke and Mark same similarities because they are independent verifications.

Kyle

Kyle,

Thanks for your comment. However, I don't agree that the reasons why scholars believe Matthew and Luke used Mark depend in any way on Methodological Naturalism!

The 3 synoptic gospels contain many passages which are nearly verbally identical to each other. Since these passages describe Jesus' deeds as well as his words, it is unreasonable to explain this simply by saying the Gospel writers were independent witnesses to the same events, since two people who independently witnessed the same events and wrote down their recollections independently, would almost certainly still not use identical sentences to describe it. In fact, there are enough such similarities in the gospels that it is astronomically unlikely that they can be independent of each other, even assuming they are all based on eyewitness testimony. Even conservative Evangelical biblical scholars tend to accept this.

So it is clear that there is some relation of literary dependence between the 3 synpotic gospels, and comparing the texts it makes the most sense to say that Mark was the first one to be written down. For one thing Mark is a lot shorter, and it makes a lot more sense that Matthew and Luke would condense it while adding more material of their own (based on their own sources), than that St. Mark would try to write a "cliff notes version" of one of the longer gospels, by removing a lot of the best material, but then puffing up the writing of the remainder (but only slightly). Also, if the 2nd century tradition is correct that St. Mark based his gospel on St. Peter's preaching, then this would be inconsistent with the "cliff notes version" hypothesis, since on that hypothesis almost none of the material in Mark would be original. On the other hand, if Mark's Gospel came first, then it makes sense that subsequent gospel writers would want to incorporate the material associated with the most important apostle.

This argument does not depend in any way on the assumption that Jesus didn't do miracles! Indeed, since the gospel of Mark contains the greatest density of miracles, saying that Mark was the first gospel to be written is hardly any kind of argument against miracles!

Occasionally I've heard laypeople propose the theory that the verbal similarities in the Gospels arose, not because the Evangelists were aware of each other's writings, but because the Holy Spirit miraculously inspired them so that they used the exact same words. But this theory has a lot of problems:

1) It seems like an unnecessary miracle, since describing the same actions of Jesus with different words (but still accurately) would probably be just as helpful to Christians.

2) The miracle would be very incomplete, since there are still a lot of divergences between the Gospels. It is clear that none of them are quoting Jesus with 100% verbal precision and completeness, since they don't give the exact same words as each other, even for the exact same events. If the goal was to prevent Christians from worrying about contradictions between the Gospels, then the hypothetical miracle didn't actually accomplish this purpose.

3) If God had wanted the Gospels to be verbally identical, then there would be no need to have 4 of them. It would have been even more impressive to have all the apostles write down the exact same Gospel, assuming he wanted to do this.

4) Why would God would do a miracle on the Gospels in order to make it look like they depend on each other, when in fact they don't? (It would be a bit similar to the people who argue that God planted the fossils in the earth in order to make it look like evolution happened, even though the earth is only 6,000 years old.)

Since God does not do miracles which are unnecessary, ineffective, and deceptive, it seems far more reasonable to assume he didn't do this, and that his inspiration of the gospels takes place at a deeper, less literal-minded level than producing verbally identical text. Here I am arguing against a miracle, but I am doing so based on supernaturalist assumptions (the character of God), not naturalist assumptions.

The argument for Mark being first, also does not depend on the existence of Q. That is, I think that even the majority of biblical scholars who reject Q, still think that Mark was probably the first Gospel to be written. Q is supposed to explain a few passages that are similar in Matthew and Luke, but not found in Mark. The hypothetical reconstructed Q (based on compiling these similar passages) actually does contain several references to Jesus' miracles, so if the two-source hypothesis is correct, Q actually gives independent reason to think Jesus performed miracles. (However, there are also viable alternatives to Q, such as saying that Luke used Matthew, or vice versa.)

A small minority of scholars believe that Matthew wrote first, largely based on other 2nd century traditions. But these scholars still think the Gospels have literary dependence on each other, they are just changing the order around.

Hi Aron, I have nothing to add or ask, but this is a great series that you are running through right now!

Thanks for taking the time to respond in detail in the comment sections. Those are mini-blog posts on their own!

Enlightening response, thank you for being so detailed. I am clearly not much of an expert in NT scholarship. Do you have any good recommendations on sources that might help a beginner like me?

Kyle,

I picked it up in bits and pieces, and unfortunately most of my books are in storage right now, so I'm afraid I can't recommend something at this time.

Hi Aron! I've been enjoying reading through this current series - good work as always!

I want to mention a few thing that I think can enhance the case for Christianity in this post:

First, I don't think you have to worry at all about you having any possible bias towards Christianity in your methodology. Even if you were to go beyond the most ridiculous estimates from the skeptical scholars of the NT, and say that all of the Gospels, Acts, and Paul's epistles were written 100 years after Jesus's death, it's clear that they would still blow everything else in history out of the water in terms of reported of miracle.

Also, in terms of Mohammad's splitting of the moon, one important point is that the hadiths reporting on it are extremely sparse (https://sunnah.com/search/?q=moon%20split) - they total to perhaps a paragraph or so, once you remove all the redundant texts. And as far as I can tell most of it is told without any context. They're nowhere near the gospel accounts of Jesus's death and resurrection in detail or the feeling of realness.

Also, the lines of transmissions do seem impressive, and I can understand why you'd feel some envy in wishing that Christianity had such a thing. But an interesting exercise is to construct similar "isnad"s for Christianity, say for the resurrection, based on different books in the NT. As far as it would go, it would look something like this:

1 Corinthians: Paul.

Gospel of Matthew: Matthew.

Gospel of Mark: Peter, Mark.

Gospel of Luke: Mary(?), Luke.

Gospel of John: John.

Acts of the Apostles: Mary(?) and Paul, Luke.

Yes, some skeptical scholars would dispute some of this, but skeptical scholars weren't writing the isnads for the hadiths either, so... yeah. I think it's clear that this line of transmission is far stronger than the one for splitting the moon. Overall, I'd put the hadith's testimony for that miracle to be below the testimony of the twelve apostles for Jesus's resurrection, by a significant amount.

This post caught my attention because I too talk about the splitting of the moon in my post arguing for the resurrection (http://www.naclhv.com/2017/04/bayesian-evaluation-for-likelihood-of_17.html - search for "splitting the moon"), which you provided some feedback on. I think we've reach pretty similar conclusions about the splitting of the moon - and if you have some time, I'd love some more feedback on my argument for the resurrection! (well, okay - it'd have to be a lot of time, which you probably don't have)

The debate about the dating of the Gospels centres on the authenticity of Jesus’ prophecies about the destruction of the Temple. Those arguing for a post AD 70 date for the Gospels are basically accusing the authors of writing fiction - at least with regard to the prophecies. I would like to make an observation that, while not conclusive, has at least some bearing on this.

Do we get the general impression that the Gospels were written by people living after the destruction of the Temple? To answer this question we need to think in general terms about the writing of fiction. It is undoubtedly the case that modern writers of fiction can be very sophisticated. But we have no reason to think that was the case 2000 years ago. Someone who lived after the destruction of the Temple would find it very hard to depict a pre-70 AD world in a consistent way, unless he was very sophisticated.

There are a number of examples in the Gospels where things happen in a very natural way - from the point of view of people who lived before the destruction of the Temple but *not* afterwards. In Mark 1:44 Jesus heals the man with leprosy and then tells him to show himself to the priests and carry out the necessary sacrifices (which would have to happen at the Temple). In Mat. 5:24 Jesus says that if you have a dispute with your brother then you should drop everything and resolve it even if you are about to make a sacrifice at the altar (which would be in the Temple, of course).

I think there would be a strong disinclination for a writer living after the destruction of the Temple to include that sort of detail. Admittedly, someone who was living after AD 70 but was determined to record the facts about Jesus regardless of his own perspective might still include such details. But that wouldn't apply to the kind of person who was inclined to make up prophecies and place them on Jesus’ lips. Just a thought.

naclev,

Thanks for your comment.

As you've guessed, I don't have time to review your entire series again. Instead I'm going to pick an entirely random and unimportant thing from the middle to critique. I don't see anything particularly implausible in the story of Honi the Circle-Drawer ending a famine through prayer to God. You say: "this is nowhere near enough evidence to overcome the small prior against a supernatural event, and we can be fairly certain that this event did not actually occur as a miracle."

You are right that the evidence for this event is nothing like the evidence for Jesus' Resurrection. But whatever unbelievers may say, from a Jewish or a Christian perspective, there is nothing particularly implausible about this event (nor does it in any way contradict Christianity, that a sincere follower of the true God should have received a favor which many pious men and women throughout history have also received!), and I while I would probably never use this particular event to try to convine an atheist that God exists, speaking as a believer I think this story is more likely true than false. Take that, Methodological Naturalism! (The one about the carob tree seems obviously legendary though, for several reasons.)

As St. James says, "The prayer of a righteous man is powerful and effective. He prayed earnestly that it would not rain, and it did not rain on the land for three and a half years. Again he prayed, and the heavens gave rain, and the earth produced its crops" (James 5:16-18). In fact, looking at the Talmudic references it seems possible that some passages in the New Testament may obliquely reference this event. Look at this passage and see if it reminds you of anything Jesus said about how we should relate to God:

"Shimon ben Shetaḥ relayed to Ḥoni HaMe’aggel: If you were not Ḥoni, I would have decreed ostracism upon you. For were these years like the years of Elijah, when the keys of rain were entrusted in Elijah’s hands, and he swore it would not rain, wouldn’t the name of Heaven have been desecrated by your oath not to leave the circle until it rained? Once you have pronounced this oath, either yours or Elijah’s must be falsified. However, what can I do to you, as you nag God and He does your bidding, like a son who nags his father and his father does his bidding. And the son says to his father: Father, take me to be bathed in hot water; wash me with cold water; give me nuts, almonds, peaches, and pomegranates. And his father gives him."

First of all, that's nowhere close to their actual estimates. I know you said that, but I'd rather people be confronted with the actual numbers than with random numbers that come from nowhere. (I've just added a line to the main article above to note the standard scholarly dating of Mark.)

Secondly, I'm not sure this is actually true. In particular it would make the letters of Paul essential fakes, and therefore basically worthless as actual reportage. What it would do to the credibility of the Gospels/Acts is more complicated, but it would certainly make them a lot less credible, and I doubt it would be rational to accept Christianity on historical grounds, in this alternative scenario you mention.

Finally, you probably shouldn't restrict "history" to ancient history. You can certainly find reports of modern day miracles that are attested with much smaller gaps than a century, and which you probably want to reject as nonsupernatural. For example, the healing miracles attribtued to Mary Baker Eddy. (There are also lots of modern miracles I would accept as authentic, but I'm giving an example that might trouble an orthodox Christian.)

---

Regarding isnads, Muslim scholars wouldn't accept most of the ones you give as valid, because according to them the chain of witnesses has to be explicitly stated by the hadith itself; not merely argued for based on people mentioned in it, or based on later tradition. Furthermore (Ahmed tells me) in the case of a written book there also needs to be a gap-free chain of oral witnesses confirming who author wrote the book and that it was transmitted correctly to subsequent generations.

Of course these concerns are rather pedantic in the case of 1 Corinthians 15, where there is no scholarly uncertainty about the author, and it's pretty clear that St. Paul was in a position to be able to know that his long list of witnesses to the Resurrection actually existed and were testifying to it; in short because he was contemporary to the events in question, with no need for long chains of transmission as in the Islamic case.

David M,

Good point. On the other hand, if the Gospel were written by a Jew only a few years after the destruction of the Temple, the author would still have spent most of their life with the Temple there, and hence one would still expect the Temple to still figure prominantly in the text, even on the cynical assumption that the bit about predicting it's destruction was totally made up.

But yes, I do think it is fairly clear that the Gospels (including John) were written down by people, or based on the testimony of people, who did still remember the Temple.

This was a great series (yes, even as a Rabbinic Jew).

What about Juche though?? I hear Kim Jong Un runs an impressive apologetics department!

Hm - strange that you would think the records for Honi as being reliable, but not the record for Jesus if they were 100 years old, even if it were just the gospels.

I do mention elsewhere that I don't think that the Jewish miracle-workers would count much against Christianity even if they were true, for exactly the reasons you mentioned. But in case of Honi, I still find the material on him to be too sparse, and too far removed in time from when they supposedly happened. Although, you linked me to some material on him that I wasn't aware of before, and some things there do make me more favorably disposed to him having performed some miracles.

Now, speaking as a believer - that is, adding on all the other evidence for the existence of the God, and how he deals with his people, ON TOP OF the historical record we have - that may be enough to bring me over to the "more likely than not" side. That may be worth mentioning in my post.

On isnads: my understanding is that the original companions didn't have to provide one, on account of them being original, as in your case for Paul. So really, if Christianity had that tradition, I think it would have looked like what I listed, which only highlights your claim that there wasn't much of a need to do so.

But for all this, I'm probably missing a lot of context on Hadith studies, and also the history of the Talmud. I'm certainly open to correction on these subjects.

The question of dating is a tricky one. It is clear that the authors of the Gospels had detailed knowledge of the setting, but we can't say for certain whether this knowledge derives from oral tradition operating over a short period of time or a long period of time (unlikely), or from preexisting written sources, or from their own memories.

In his letter to the Smyrnaeans, Ignatius says the following:

“For I know that after His resurrection also He was still possessed of flesh, and I believe that He is so now. When, for instance, He came to those who were with Peter, He said to them, ‘Lay hold, handle Me, and see that I am not an incorporeal spirit.’”

Ignatius, who was writing around AD 110, certainly knows the *tradition* that is recorded in Luke's Gospel but we can't say for certain whether he knows Luke's Gospel itself. It is a debated issue among scholars.

I favour early dates for the Gospels, but I don't think we actually *need* early dates. The important thing is that the reliability of the Gospels can be demonstrated.

I never said I thought the evidence for Honi was greater than the evidence for the Resurrection would be if the Gospels were written 100 years later. The opposite is in fact the case. But priors come into it as well. Given that I already believe in Christianity, the priors for Honi are not very low.

Efraim,

I mentioned Juche briefly in part II, although I was pretty dismissive.

Hello Aron,

You wrote because we already know that Jesus sometimes adapted illustrations from other sources and I'm very interested in which ones He adapted or what sources used. Could you point me to somewhere I could read more about it?

Regarding another issue: I'm wondering whether I could translate some of your articles into Spanish for some of my friends.

David D.,

For example, Luke 14:7-11 is an expansion of Proverbs 25:6-7, and there are many other examples of Jesus adapting biblical material.

-That the Golden Rule sums up the Torah was previously said by Hillel the Elder, and his teaching about the Two Great Commandments appears to have been the common understanding of rabbis at his time (compare Luke 10:27 with Mark 12:28-34).

-"Bind him hand and foot and cast him into the outer darkness." (Matt 22:13) alludes to the nonbiblical Book of Enoch, where it refers to punishment of the rebel angel Azazel (here we see Jesus reworking an element of a fictional story without thereby endorsing the entire book from which it was taken).

-"Look, I send you out as sheep among wolves. Therefore be wise as serpents and harmless as doves" (Matthew 10:16) seems to me to hearken back, at least in a general way, to animal fables such as in Aesop. (The thematically similar "wolf in sheep's clothing" (Matthew 7:15) inspired a story sometimes attributed to Aesop, but it appears to actually be post-Christian.)

- In the Parable of the Minas (Luke 19:11-27), the frame story about a man seeking to be appointed king seems to be partially based real historical events that would have been familiar to the audience, since the kings in the Herodian dynasty had to go to Rome in order to be appointed kings over the land of Israel.

Since Jesus was not just fully divine but also fully human, it is reasonable to expect that he was causally influenced in his human understanding by the stories and events he had grown up with. But this in no way takes away from the authoritative nature of his teaching, since he only used this material in ways which glorified the Father. (That being said, there are a lot more allusions to pagan sources in the teaching of Paul, who had a very wide ranging education, compared to Jesus who is much more Hebraic in his temperament.)

Please feel free to translate my articles into Spanish with my blessings, just include a link back to the original source!

OT:

Hi Aron,

What do you think of the proposed CALTECH expt on black-holes-wormholes using quantum circuits? Apparently they are using your paper. Thanks.

Kashyap Vasavada

Have you come across William Paley’s View of the Evidences of Christianity? In https://ccel.org/ccel/paley/evidence.iii.ii.i.html he identifies two types of distinctions that apply to evidence for miracle-claims: 1) distinctions on the evidence for some event, 2) distinctions on the evidence for interpreting that event as miraculous.

Distinctions which relate to the evidence:

1. Such accounts of supernatural events as are found only in histories by some ages posterior to the transaction, and of which, it is evident. that the historian could know little more than his reader.

2. We may lay out of the case accounts published in one country of what passed in a distant country without any proof that such accounts were known or received at home.

3. We lay out of the case transient rumours.

4. We may layout out the case what may be called naked history [i.e., accounts in a historical vacuum].

5. A mark of historical truth, although only a certain way and to certain degree, is particularity in names, dates, places, circumstances, and in the order of events preceding or following the transaction.

6. We lay out of the case such stories of supernatural events, as require, on the part of the hearer, nothing more than an otiose assent; stories upon which nothing depends, in which no interest is involved, nothing is to be done or changed in consequence of believing them.

7. We have laid out of the case those accounts which require no more than an a simple assent; and we now also lay out of the case those which come merely in affirmance of opinions already formed.

Distinctions which relate to the miracles:

1. It is not necessary to admit as a miracle what can be resolved into a false perception.

2. It is not necessary to bring into the comparison what may be called tentative miracles [i.e., lucky successes out of many attempts].

3. We may dismiss from the question all accounts in which, allowing the phenomenon to be real, the fact to be true, it still remains doubtful whether a miracle were wrought [e.g., events with an apparent scientific explanation].

These could be supplemented with other considerations, e.g., does the event have any context around it in which we might expect God to act?

“The evidence does not seem to support the extravagant claim by orthodox Muslims that the Quran was preserved perfectly, since there is plenty of evidence for variant readings among early Muslims. (Mohammad is said to have explained some of the variant readings among different Muslim groups by claiming that the Quran had been revealed in 7 different Arabic dialects, but this could easily have been an ex post facto rationalization in order to keep peace in the community.) “

Variant readings somehow contradicts prefect preservation is common missionary claim rejected by scholars in the relevant field , As for the hadith that explains variant reading is too strong to be post rationalisation